Wednesday, August 27, 2014

My Top 100 Directors: 60-41

60. Terence Malick (Tree of Life; Thin Red Line)

There really are few directors quite like Terrence Malick. In terms of my 5 film rule, it took Malick all of about 38 years to direct 5 movies. Despite the scores of praise heaped on his first two films, Badlands and Days of Heaven, I believe it is when Malick came out of his self imposed exile that his truly great work began. Thin Red Line, The New World and my personal favorite Tree of Life are all among the best films of the last two decades. Malick’s style also began to emerge, and with Tree of Life as well as Line, he really stuck a big middle finger up to conventional narrative and made films based more on feeling than story. Even if we get a film a decade, they’re almost always worth it.

59. Gus Van Sant (Elephant; Last Days)

Gus Van Sant has been among the leading independent directors for decades. His Drugstore Cowboy and My Own Private Idaho were masterpieces of Generation X cinema. Van Sant was eventually tempted by things like money and more high profile gigs, and has even earned himself some recognition by the establishment for his work on Good Will Hunting and Milk. The smaller Van Sant films are always my favorites, and with some films like Elephant, Last Days, or Paranoid Park few directors are as relevant and good. He’s become something of a master of long takes, and well that’s something I always appreciate.

58. Frank Capra (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington; It Happened One Night)

Although his major films all seemed to have a central theme, Frank Capra is probably the central figure in my greatness through great films debate. From It Happened One Night through It’s a Wonderful Life, there was no better director in all of Hollywood. He pulled down 3 best director Oscars in 5 years, a mark that will probably never be equaled, and on top of that all three films are still amazing today. It Happened One Night might still be the greatest of all screwball comedies, and every movie and show about insider politics owes a special debt of gratitude to Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, for my money the best film from the legendary year of 1939.

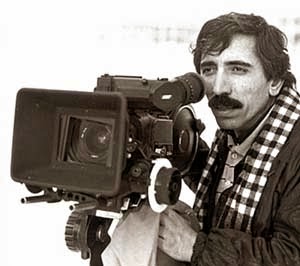

57. Mohsen Makhmalbaf (Marriage of the Blessed; The Cyclist)

There are always debates amongst film scholars between various figures. Do you go for Hou over Yang, Godard over Truffaut, Keaton or Chaplin, Szabo over Jancso, or in the case of Iranian cinema Makhmalbaf or Kiarostami? We can argue this point from now until forever but there has never really been any debate internally. Perhaps Kiarostami has enjoyed a more overall consistent career longer, but his high points to me never came close to Mohsen’s. Whether it was Marriage of the Blessed, Boycott, The Cyclist, Gabbeh, Moment of Innocence etc. his work has been the highpoint of Iranian cinema. Stylistically the man is a marvel, and much of what I know about Iran has come from his extraordinary work.

56. Ousmane Sembene (Xala; Camp de Thiaroye)

The unquestioned master of African cinema. Senegal’s Ousmane Sembene was an accomplished author before becoming his nations first true filmmaker, and he spent the better part of five decades making the best of all African movies. His films are highly critical, often full of dark comedy, and he has never allowed the many financial limitations get in the way of some truly extraordinary stories. If reading his name is making you scratch your head, please check out some of his work.

55. Sergei Eisenstein (The General Line; Battleship Potemkin)

We’re getting into some legendary territory here with Eisenstein, the master of montage and the figurehead of the Soviet film movement. Although he managed to complete three excellent sound features, Eisenstein’s greatest legacy remains his silent work. There might not be a more influential silent film than Potemkin, and Eisenstein’s films and writings have become a veritable textbook in film editing. His later work pioneered deep focus photography and established a unique bit of versatility.

54. Bela Tarr (Satantango; Damnation)

In the realm of depressing and dreary Eastern European cinema filled with bleak landscapes, long shots, and sad people Bela Tarr is in a class all of his own. Long a fan of lengthy takes, starting with 1987’s Damnation Tarr decided all his films looked better in black and white and hasn’t looked back since. Satantango is over 7 hours of awesomeness and before there’s a single cut in the film it’s a pretty clear indicator of whether or not Tarr’s style is for you. He is the extreme continuation of earlier long take existential European art house filmmakers and his predecessors I’m sure would be proud.

53. Frederick Wiseman (Public Housing; Titicut Follies)

When it comes to cinema verite the only name you really ever need to know is Frederick Wiseman. It’s hard to rank Wiseman amongst other filmmakers because he is the only one on this list whose primary work is in documentaries. Also he is nowhere near the master manipulator that most documentarians are from Flaherty to Moore. Wiseman picks a subject, films it and offers no commentary or analysis. There are no talking heads, no clever edits just his subject in it’s natural habitat. Over the last nearly 50 years he’s had some pretty exceptional subjects as well, which might help explain why his films are so damn good. I’ve seen probably two dozen of his movies and I have no idea how he manages to make them so compelling and worthwhile. Although with many directors on this list their greatest gift is their subtlety.

52. Max Ophuls (La Ronde; There’s No Tomorrow)

Whenever a director can make the claim that he was a huge influence on Stanley Kubrick I need to pay attention. Max Ophuls spent his career bouncing from one country to another carrying his extraordinary style with him everywhere. Even his few American movies remain among the best of the late 40s. Ophuls hit his stride in the 50s in France during the twilight of his career where his four late films perfectly captured his essence. Ophuls dealt mostly with the upper classes, in period pictures, romance, and filmed all of his movies as if they were one extended waltz. Ophuls was also one of those masters of long takes long before it was fashionable, and his style truly stood out amongst all his peers.

51. Yasujiro Ozu (Early Summer; Good Morning)

Amongst all the many idiosyncratic foreign directors out there, few created a style unto themselves quite like Yasujiro Ozu. Frankly put, no one seems to have even attempted to make a movie like Ozu in the 50 odd years since his passing. The king of Japanese cinema, Ozu spent his early days bouncing around different genres before eventually settling on the Japanese family structure. Many of his films are simply different aspects of family relationships and so many of those films are transcendent. I’ve always been a fan of the films that seemed a little out of character, whether it be Where are the Dreams of Youth?, Tokyo Twilight, or Good Morning, but it’s hard to argue with what his bread and butter were.

50. D. W. Griffith (Intolerance; Birth of a Nation)

When it comes to historical importance, few can even begin to match the legacy of D. W. Griffith. Granted much of that legacy was built up by Griffith himself, but in the 1910s the man had no peers in all of world cinema. Even today Intolerance remains one of the all time greatest films, and as polarizing as Birth of a Nation might be, it’s hard to deny what an extraordinary achievement it was in cinema. Griffith’s post Intolerance films are also pretty damn incredible, and he even managed to produce some unfairly overlooked sound films before fading into obscurity. You can argue though that without Griffith America might not have ever become the juggernaut of world cinema it has been.

49. Miklos Jancso (The Red and the White; Red Psalm)

Remember my comment about Szabo over Jancso a few entries back? Well this is my take on that debate. Miklos Jancso died earlier this year, but not without establishing himself as the greatest of all Hungarian directors. Jancso focused many of his films on historical events, and like Tarr after him loved to use extremely long and elaborate tracking shots. His films were often allegories of Soviet occupation and one of his most prominent themes was the abuse of power in his movies. From a purely visual sense though it was always amazing to watch this man work.

48. Alfonso Cuaron (Children of Men; Y Tu Mama Tambien)

You might be noticing a pattern by now of my fondness for directors who can shoot long takes. Cuaron finally got himself a best director Oscar for his work on last year’s Gravity, and frankly it’s about damn time. Gravity is one of those rare films made where you scratch your head an wonder just how the hell they did it. In today’s Hollywood where everything up to and including the moon are CGI, it takes a lot to really impress people, and that’s what Gravity did. It doesn’t hurt that he also directed the best Harry Potter film (Prisoner of Azkaban), and I can’t praise Children of Men enough. As a filmmaker though I’m not sure if anyone is capable of making films as impressive as Cuaron right now.

47. Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise; Dazed and Confused)

It’s often a lame cliché to say someone is the voice of a generation, but when that generation is X, Richard Linklater seems to perfectly fit that description. From his first film, Linklater has been making uniquely personal films for those children of the early 90s. His animated work is extraordinary as well, and I can’t begin to recommend Waking Life and Through a Scanner Darkly enough. Dazed and Confused is still the ultimate in nostalgic high school comedy, and I haven’t even mentioned the Before trilogy. Before Sunrise, as well as it’s two follow-up films Before Sunset and Before Midnight are about the best thing to happen to cinema in the past twenty years. Oh yeah, and there are plenty of extremely long takes in those films as well, wouldn’t want to break the streak.

46. Satyajit Ray (Pather Panchali; Distant Thunder)

Some topics of cinema aren't even up for debate, like who the master of suspense was or in this case who was India's greatest filmmaker. Satyajit Ray became an icon of international cinema on par with Akira Kurosawa and Federico Fellini during the 50s and maintained his status as the most important director in India for the next five decades. His films were a stark break from the mainstream Bollywood films, and he took more of a cue from Jean Renoir and the neo-realists, than his peers. Although best known for his Apu trilogy, Ray’s 60s and 70s work might have been even better. The absolute master of Bengali cinema.

45. F. W. Murnau (Sunrise; Faust)

Another in a long list of silent film pioneers, F. W. Murnau might damn well be the best of them all. During the 1920s Murnau became arguably Germany’s greatest filmmaker in a decade known for amazing filmmakers. He produced one of the most iconic horror movies ever in Nosferatu, which still might be the best vampire movie ever made. Before leaving for the US, Murnau also made the nearly title-less masterpiece The Last Laugh and the only truly exceptional adaptation of Faust. His first film in Hollywood, Sunrise however is the reason he’s on this list. It is on the short list of the greatest silent films of all time and is absolutely perfect. Sadly Murnau died a few years later before having a chance for further greatness.

44. Jacques Rivette (Celine and Julie Go Boating; Up Down Fragile)

Of the original five Cahiers du Cinema critics turned directors in the French New Wave, all took remarkably different paths. For Jacques Rivette, the most criminally overlooked of the bunch, he made a series of improvisational films with exceptionally large running times and a style unlike any other. His films have usually suffered a fate of poor distribution and for a very long time Out 1 (his 12 hour opus) was considered more the stuff of legend. I happened to be present for possibly Chicago’s only screening of the film over two days and it was one of those truly incredible cinematic moments. I’ve since tracked down as many of his films as I can and very rarely am I disappointed. His work is often challenging, frequently head scratching, but once in a while it’s just phenomenal.

43. Peter Watkins (La Commune: Paris 1871; Punishment Park)

The last time I made this list I might not have even known who Peter Watkins was. Over the last decade his work has probably been the high point of my movie watching. He has specialized in the mockumentary, but his films generally focus on two scenarios, either historical recreation, or hypothetical Orwellian narratives. All of his films are social commentaries, and he shoots his films like verite documentaries creating an eerie sense of reality. My first introduction to him was Punishment Park, and I honestly had to look up whether or not it was based on a real place after watching it, his movies are that damn good.

42. Francois Truffaut (Jules and Jim; The 400 Blows)

Another new wave veteran, Francois Truffaut enjoyed probably the greatest commercial success of his directors because at the end of the day he made movies he would have wanted to see growing up. Often times this resulted in lighter faire, and crowd pleasing efforts, but there certainly were some great films among them. His semi-autobiographical Antoine Donel films, particular The 400 Blows are French cinema at it’s finest. Few French directors captured the joy and wonder of cinema quite like Truffaut.

41. Roberto Rossellini (Voyage in Italy; Open City)

The second of my big 4 Italian directors, Roberto Rossellini was there at ground zero for neo-realism. Open City remains one of the most astonishing films of the 40s in terms of it’s content, violence, and in the simple wonder of how the hell it even got made. In the process Rossellini became a one man cinematic revolution. He did eventually outgrow the style, and his work with Ingrid Bergman helped usher in a whole new era of world cinema, the existential angst of the upper classes. Rossellini managed to influence damn near every filmmaker who came after him, and through him future directors like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni got their starts.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment